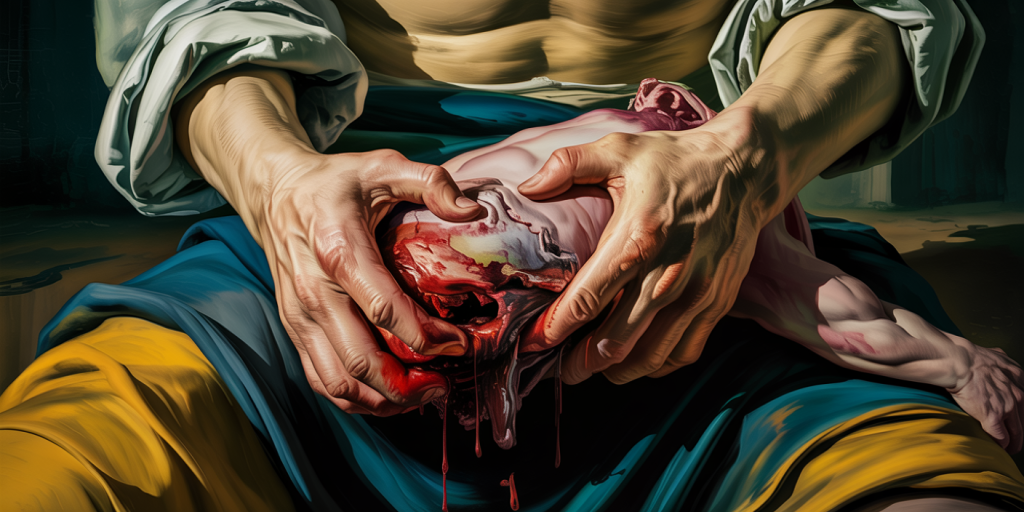

Saturn Devouring His Son by Francisco Goya

Silence is not always golden—it can be devoured. In the cavernous world of Francisco Goya, silence is not a void, but a shivering pulse, a hush before the scream. In Saturn Devouring His Son, the quiet is torn open. The canvas swallows sound, time, light, and logic. What remains is a vision that bites, that gapes, that speaks through its brutal hush.

Goya did not merely paint a myth; he painted a collapse. A father devours his own legacy, eyes wide with madness, mouth foaming with fear. Yet the most deafening part of the image is not the blood, nor the act—it is the pause between bites. It is the moment where the time-stained silence is louder than time itself.

Table of Contents

- The Canvas as a Crypt

- Flesh Torn, Time Unraveled

- Eyes That Have Forgotten Mercy

- Hands Stained with History

- A Palette of Ash and Screams

- The Son Without a Face

- Saturn’s Hair: Storms of Regret

- Darkness as Devourer

- The Stillness of Madness

- Devouring the Future

- The Body as a Clock

- Gravity of the Brushstroke

- The Wall that Bled

- Echoes of the Spanish Psyche

- Composition in Collapse

- Light That Refuses to Save

- When the Frame Becomes a Coffin

- The Horror Behind the Myth

- Ritual of Paint and Shadow

- The Wound That Will Not Heal

The Canvas as a Crypt

Goya did not intend this to hang in a gallery. It was painted on the wall of his home—his own mausoleum of thought. The canvas is not a window, but a tomb, a sealed chamber where the air is thick with dread. It’s less a painting than a burial, a place where images rot and echo.

Flesh Torn, Time Unraveled

Saturn’s fingers rip through time as if it were muscle. The torn body represents more than his son—it is tomorrow, lineage, hope. Each bite is a second swallowed. Goya paints flesh as if it were a scroll being erased. The myth becomes prophecy, and prophecy becomes decay.

Eyes That Have Forgotten Mercy

Saturn’s bulging eyes are not sane. They are ruptured stars in a collapsing sky. Goya gives us no comfort in them—no flicker of remorse, no glint of humanity. Only panic. Only a bottomless hunger that forgot what it fed upon. The eyes accuse the void itself.

Hands Stained with History

The hands, enormous and claw-like, are painted with speed, desperation. They clutch not just meat but memory. Each finger carries centuries of blood—personal, political, ancestral. Spain’s own hands. Goya’s own hands. Hands that painted peace once, now stained with screams.

A Palette of Ash and Screams

Goya’s colors are sparse—earth, blood, bone. No golden myth here. Just grays and browns, as if the entire painting were composed from the ashes of burned time. The red is not vivid—it is dry, as if the painting itself is running out of blood.

The Son Without a Face

The devoured son has no head. No features. No voice. He is the faceless future—anonymous, dismembered. Goya denies him humanity. This is not a person being eaten, but a possibility. The loss of identity is the cruelest amputation.

Saturn’s Hair: Storms of Regret

His hair, wild and white, resembles thunder—lightning that struck too many times. It bristles with static guilt, a crown of chaos. The strands seem to move even in the stillness of the frame, like memories refusing to rest.

Darkness as Devourer

More than Saturn devours his son—the darkness devours them both. The background is not blank; it is a black hole. It eats the edge of the figure. There is no floor, no ceiling, no landscape. Only oblivion. The absence becomes a participant in the violence.

The Stillness of Madness

Nothing moves in the painting, yet everything trembles. The madness is frozen, like a scream caught in ice. Goya captures the moment after motion, where terror becomes statue, where time halts to witness the unthinkable.

Devouring the Future

Saturn is not just killing—he is preventing. Preventing rebellion, prophecy, succession. Goya paints paranoia itself. The future must not grow, so it must be consumed. This is political, personal, eternal. Tyranny always eats its children.

The Body as a Clock

The son’s limbs are arranged not just in horror but in time. One arm, one leg, each pointing like a broken clock hand. The devouring is cyclical, and Goya’s composition spins us in that terrible spiral. The body keeps the time that Saturn destroys.

Gravity of the Brushstroke

The brushstrokes are not delicate—they are scratched, poured, bruised. Goya paints as if he’s exorcising. Each stroke falls heavy, almost accidental, but with purpose. The paint itself seems to be screaming under his hand. This is not technique—it is confession.

The Wall that Bled

Originally painted directly on plaster, this work was not meant to be shared. It was a private exorcism. The wall bled Goya’s vision. Transferred to canvas later, it carries its trauma like an echo. The surface is haunted with its origin.

Echoes of the Spanish Psyche

This painting is not just mythological—it is national. Post-Inquisition Spain, post-Napoleonic trauma, post-hope. Saturn becomes Spain, Goya becomes witness. The devouring is colonial, religious, patriarchal. The silence is cultural. The horror is historical.

Composition in Collapse

Goya breaks every rule of balance. Saturn leans into the void, the body sprawls downward. No symmetry, no ground. The painting wants to fall out of its frame. Its asymmetry is deliberate: it mirrors the collapse of reason.

Light That Refuses to Save

There is light, yes—but it is not redemptive. It falls on Saturn’s face, on the meat in his hands, illuminating the grotesque. It saves nothing. It accuses. Goya uses light as interrogation, not salvation. Even radiance is cruel here.

When the Frame Becomes a Coffin

The proportions are tight, suffocating. No room to breathe. The image presses against the frame as if it were trying to escape—or drag us in. The frame becomes a coffin. The viewer is not outside the image, but buried with it.

The Horror Behind the Myth

Goya knew the myth, but he wasn’t illustrating—it was a pretext. He paints not Saturn, but the horror of being human, of being ruled by fear. Myth is only a skeleton here. The flesh is modern, raw, immediate.

Ritual of Paint and Shadow

This is not merely a painting—it is ritual. Paint becomes sacrament, shadow becomes prayer. Every inch is liturgy for a god of silence and loss. Goya enacts his trauma, drips it onto the wall. It is not performance. It is mourning.

The Wound That Will Not Heal

Even now, centuries later, the wound gapes. The painting is still bleeding. Goya gave us not a scene to observe, but a wound to remember. And wounds, unlike images, do not fade. They deepen. They echo. They bite.

FAQ

Who was Francisco Goya?

Francisco Goya (1746–1828) was a Spanish painter and printmaker, considered a master of both classical and modern art. His later works, including the “Black Paintings,” reflect a profound disillusionment with society and personal torment.

What is the ‘Black Paintings’ series?

The “Black Paintings” were a group of murals painted directly onto the walls of Goya’s home between 1819 and 1823. They include themes of madness, darkness, and despair, reflecting his inner state and political pessimism.

What myth is being depicted?

The painting represents the myth of Cronus (Saturn), who devoured his children to prevent them from overthrowing him. Goya reimagines this act with intense psychological horror.

Why does the son have no head?

The facelessness intensifies the horror and symbolism. It erases identity, suggesting that the son represents not a person, but future, innocence, or hope itself.

Why did Goya paint this in his home?

These were private works, not meant for public display. They reflect his inner chaos and his solitude. Painting became his language when words failed.

When Silence Screams – Final Reflections

Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son is not a tale—it is a tremor. A rupture in the skin of art. It devours interpretation as much as it does myth. We look, but we are also consumed. The silence around Saturn’s scream becomes our own.

This painting lives in the space between madness and memory, brushstroke and bruise. It reminds us that horror is not only seen—it is felt, inherited, breathed. And though time may pass, the silence Goya painted has teeth. It still bites.