Rodin Sculpts the Regret That Was Never Spoken

There is a silence that hardens into bronze. It does not shout, it trembles. In the hands of Auguste Rodin, remorse becomes matter, and the unsaid is given a body — tense, bent, burning. He sculpts not the moment of despair, but the seconds just before it escapes the throat, when the soul hesitates on the verge of confession. Regret, for Rodin, is not a concept. It is a posture. It is flesh folded inward, a weight that curves the spine of thought.

His sculptures do not rest on pedestals — they pulse. They carry warmth even in metal, as though the gesture never ended. “Rodin Sculpts the Regret That Was Never Spoken” is not about a single figure, but a choir of forms: The Burghers of Calais, The Thinker, The Prodigal Son, The Gates of Hell. Each of them whispers through clenched hands and hollow chests. Each one mourns something that words refused to carry.

Table of Contents

- Bronze That Breathes With Guilt

- Shoulders Heavy With What Ifs

- The Spine Curved Like a Question

- Hands That Speak in Silence

- Eyes That Refuse to Close

- The Gravity of Incompletion

- Poses That Fold Into Themselves

- Texture as Emotional Terrain

- Light Crawling Over Bronze

- The Poetry of the Torso

- Weight Without Witness

- The Elegance of Rawness

- Echoes in The Gates of Hell

- A Thinker Trapped in Thought

- The Moment Before the Fall

- Unfinished as a Moral Choice

- Clay That Remembers the Fingertips

- Faces Melted by Memory

- Stillness That Vibrates

- Redemption Without Resolution

Bronze That Breathes With Guilt

Rodin’s bronze is not static. It breathes, sweats, recoils. Unlike the polished calm of classical sculpture, his metal quivers. It is cast from emotional fire, not merely physical form. His surfaces are not smoothed, but scarred. This texture is memory made visible.

The way light clings to it, the way shadow burrows in creases — it evokes a sense of breathing grief. The bronze, though hardened, feels soft where sorrow pools. Rodin’s genius lies in his refusal to seal emotion. He leaves it open, glowing.

Shoulders Heavy With What-Ifs

Few sculptors have given as much weight to a shoulder. In Rodin’s figures, they are never square or proud. They slope, collapse, ache. They carry burdens that have no physical form but crush nonetheless.

Symbolically, the shoulder becomes the shelf where regret rests. Anatomically, it dips not from gravity alone, but from the density of reflection. These are bodies bearing truths they could not say aloud.

The Spine Curved Like a Question

Rodin’s postures are never upright. The spine, usually a symbol of strength, becomes a line of vulnerability. It curves, twists, bends — as if asking a question the mouth dare not form.

This curvature is compositionally powerful. It directs the eye downward, inward. It refuses confrontation. It asks the viewer not to judge, but to witness.

Hands That Speak in Silence

More than any other part, Rodin’s hands hold the narrative. They clutch the face, press against the chest, open midair, frozen in confession. They are language in gesture.

Technically, he modeled hands separately, returning to them obsessively. They are oversized, exaggerated, raw. In The Burghers of Calais, each hand is a small tragedy — wringing, dangling, resisting.

Eyes That Refuse to Close

Rodin rarely carves eyelids in full rest. The eyes remain half-open, startled, unfinished. They look not outward but inward, or into some space beyond comprehension.

There is no gaze toward the heroic. Instead, the gaze collapses. It avoids. It remembers. Eyes like this do not seek resolution. They hold witness to the unresolved.

The Gravity of Incompletion

Rodin embraced the unfinished. Torsos without limbs. Heads without bodies. Surfaces left rough. For him, incompletion was not failure — it was truth. Grief is never finished. Regret is always partial.

The material left undone speaks louder than the completed. It invites the viewer to complete it emotionally. What is missing becomes a mirror.

Poses That Fold Into Themselves

Rodin’s figures fold. They do not stretch. They cave in. A knee meets a chest. A face sinks into hands. A body hugs itself like a child who knows they will not be consoled.

This self-embrace is not comfort. It is collapse. Compositionally, it draws the gaze inward, forming spirals of emotion that resist heroic linearity.

Texture as Emotional Terrain

Rodin did not chase smoothness. His surfaces churn. Bronze looks like clay, like muscle, like memory. Each ridge is a tremor. Each bump, a stutter in time.

Texture becomes more than skin — it becomes a landscape of interiority. His sculptures ask not to be admired, but touched.

Light Crawling Over Bronze

Light interacts with Rodin like breath on glass. It slides, hesitates, deepens. His forms are never flat, so shadow becomes a collaborator. It paints moods, hours, silences.

Bronze gleams on high points, sinks into recesses. It reminds us that every emotion has its surface and its depth. That which shines also shivers.

The Poetry of the Torso

Even when limbs are absent, the torso tells everything. In Rodin, it is the drum of sorrow, the container of all the unsaid. It twists, leans, contracts. It is the architecture of ache.

He saw the torso not as incomplete, but as concentrated. It holds the soul’s volume in the cavity of ribs and the tilt of a shoulder blade.

Weight Without Witness

Many of Rodin’s figures carry grief in solitude. They are not seen by others in the scene. They are turned inward, alone in crowds. There is no dialogue. Only monologue of the flesh.

This isolation is not stylistic — it is thematic. The burden of unsaid regret is always lonely. Even in a group, each figure is an island.

The Elegance of Rawness

Rawness, for Rodin, was beauty. He made elegance out of imperfection. A rough edge was not a flaw, but a breath. A visible seam was not a mistake, but a heartbeat.

This refusal of classical polish gave birth to modernity. He let the sculpture show how it was made. Emotion became part of the process, not just the product.

Echoes in The Gates of Hell

The Gates of Hell is a cathedral of remorse. Figures fall, cling, crawl. Dante’s vision becomes Rodin’s stage for eternal regret. Each body screams without sound.

The Thinker, perched above, is not triumphant. He is trapped. The door is not passage, but prison. Rodin sculpts hell not as punishment, but as permanence of sorrow.

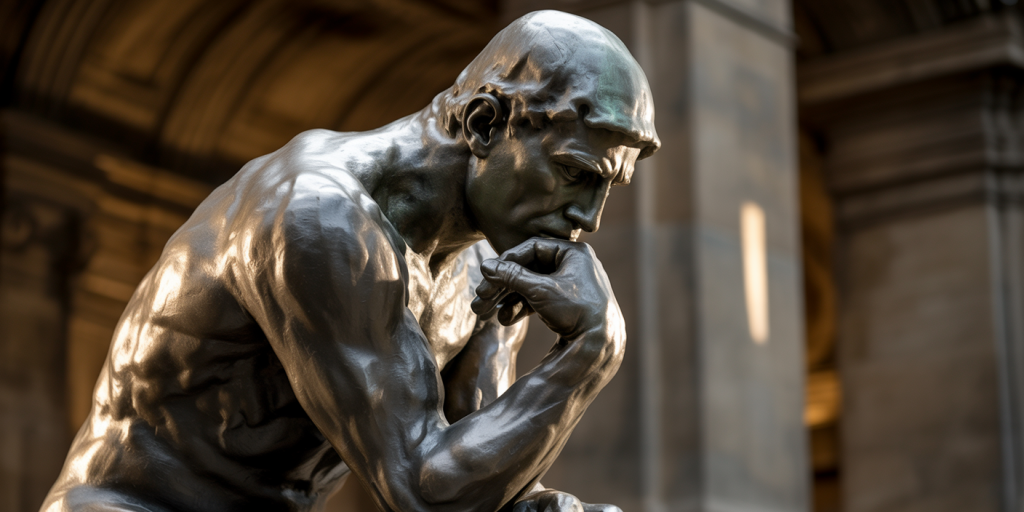

A Thinker Trapped in Thought

The Thinker is often misunderstood. He is not a philosopher. He is a man consumed. His hand clutches his mouth, not in contemplation, but in hesitation.

His muscles are tense, not relaxed. His brow furrows not in peace, but pain. This is a portrait of someone who knows he should have spoken, but didn’t.

The Moment Before the Fall

Rodin captures not the fall, but the instant before. The body that knows it will collapse. The breath held too long. The back beginning to bend.

This moment is emotionally potent. It is the edge of decision, the pause before apology, the silence before the scream.

Unfinished as a Moral Choice

His incomplete forms demand participation. They say: feel this. Imagine this. Carry this weight. Rodin does not provide closure. He provides opening.

In this way, his sculptures become ethical. They ask the viewer to engage, to respond, to remember that not all grief has grammar.

Clay That Remembers the Fingertips

Rodin’s clay models were never erased. He let the fingerprint remain. He let the push of thumb, the scrape of nail, the tremor of hand be seen.

This is not laziness. It is philosophy. The maker and the made remain in dialogue. The sculpture remembers the moment of becoming.

Faces Melted by Memory

His faces are rarely symmetrical. One side sags, the other clenches. They are warped not by fire, but by memory. These are faces where sorrow took residence.

Emotion disfigures, and Rodin honors that. He sculpts the consequences of feeling. He lets regret leave its fingerprints on the cheekbone.

Stillness That Vibrates

Though still, his figures are never static. There is movement beneath the skin. A tremor in the calf. A twist in the shoulder. A breath held mid-sentence.

This vibrational stillness is rare. It makes bronze feel like muscle. It makes silence feel like song.

Redemption Without Resolution

Rodin does not offer happy endings. His work does not solve sorrow. It sculpts it. His art does not redeem through conclusion, but through exposure.

In this way, he tells the truth. Some regrets remain. Some apologies never spoken. Some gestures are all we have.

FAQ – Questions and Answers

Who was Auguste Rodin?

Rodin (1840–1917) was a pioneering French sculptor known for expressive, emotionally charged works like The Thinker, The Kiss, and The Gates of Hell. He revolutionized modern sculpture by embracing texture, incompletion, and psychological depth.

Why is Rodin important in art history?

He broke with classical tradition, emphasizing raw emotion over idealized form. His work influenced generations of sculptors and ushered in modernist approaches.

What is The Burghers of Calais about?

It depicts six citizens sacrificing themselves during the Hundred Years’ War. Rodin portrayed them not heroically, but vulnerably, each lost in personal despair.

What does The Thinker represent?

Often interpreted as deep contemplation, it also suggests hesitation, regret, and psychological struggle — a man locked within his own silence.

Why did Rodin leave works unfinished?

He believed incompletion conveyed emotional truth. The absence invited the viewer to participate emotionally and imaginatively.

Final Reflections – The Sculpture of the Unspoken

Rodin sculpted what others would not dare say. He gave body to silence, gesture to guilt, form to the ache that follows unsent letters. His figures do not explain. They inhabit. They tremble. They remember.

In every rough edge, in every bowed head, in every hand reaching toward nothing, there is a truth too soft for language. A regret too human for marble. And in that, Rodin does not show us heroes. He shows us ourselves.