From Clay to Being, Aleijadinho and the Mystique of the Wounded Form

By Aleijadinho

When Clay Whispers the Soul

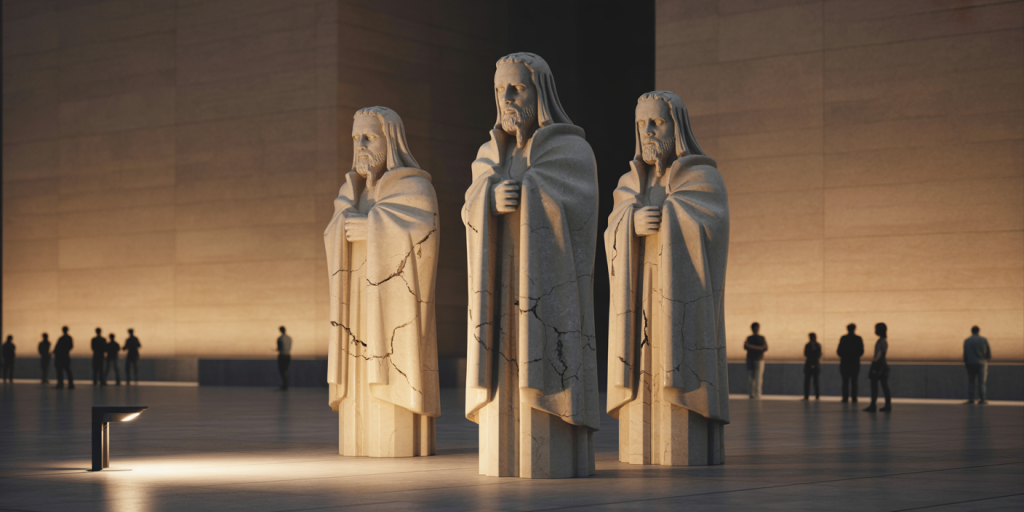

There are forms that do not merely sit in space—they ache in it. Forms that seem to remember pain. Forms that pray without words. In the sculptures of Aleijadinho, each surface bleeds devotion, and each fissure tells of both divine yearning and human fragility. The stone becomes flesh not by polish, but by wound.

To gaze upon his prophets or passion figures is to be seen by sorrow itself. They are not simply biblical icons—they are vessels that hold centuries of struggle, faith, and silence. Their eyes do not look; they mourn. And in that mourning, we too become shaped, as though our bones were softened by the tears of the baroque.

Table of Contents

- The Hand That Sculpted in Pain

- Eyes Carved from Silence

- When Saints Bear the Weight of Stone

- Baroque as a Language of Wound

- Cracks that Speak of Eternity

- Clay and the Breath of the Divine

- Sacred Asymmetry and Holy Imperfection

- The Earth as Witness and Material

- Sculpting in Prayer, Living in Suffering

- Light, Shadow, and the Drama of Belief

- Expression Beyond Flesh

- A Face Made of Dust and Fire

- The Cross that Leans but Does Not Break

- Emotional Chisel, Spiritual Hammer

- The Human as Altar

- When Form Kneels

- Texture as Testimony

- Architecture of Faith in a Body

- Sculpted Testaments in Ouro Preto

- The Voice of the Baroque Echoes Still

The Hand That Sculpted in Pain

Aleijadinho’s hands, twisted by illness, became vessels of transcendence. What others might have hidden, he sanctified. Even as his body betrayed him, his spirit became more precise. He strapped tools to stumps, sculpting not despite pain—but through it.

The agony in his fingers becomes the pathos in his figures. The chisel, guided by affliction, does not erase suffering—it sanctifies it. And thus, the creator becomes kin to the creation: broken, believing, eternal.

Eyes Carved from Silence

The eyes of Aleijadinho’s figures are not anatomically accurate—they are emotionally absolute. Deep, shadowed, slightly downturned or raised in desolate appeal, they do not see—they remember.

There is silence in them. Not the absence of sound, but the fullness of it. These eyes seem carved by years rather than tools, by prayers rather than sketches. Their gaze pierces not outward but inward, toward the infinite wound of the soul.

When Saints Bear the Weight of Stone

His saints do not float in divine ecstasy. They lean forward. They bend. Their garments drag heavy with earth. They carry not only the cross, but the centuries of colonial faith, of African prayers, of Indigenous soil.

These are saints of weight. Their postures bear the burden of time. They are not unreachable—they are exhausted companions. And in their weariness, they are holy.

Baroque as a Language of Wound

Baroque is drama. But in Aleijadinho’s hands, it becomes confession. The twisted forms, exaggerated gestures, and charged tension all speak the language of inner rupture. The divine here is not triumphant—it trembles.

His baroque is not ornamental; it bleeds. It is visceral, raw. It drips candlelight and cries incense. And through this emotional density, it brings heaven closer—not by idealization, but by sharing in the ache of the flesh.

Cracks that Speak of Eternity

The soapstone he used does not age kindly. It cracks, weathers, crumbles. But Aleijadinho’s art lives in those cracks. The decay becomes part of the expression, a slow performance of erosion that mirrors spiritual perseverance.

Time becomes visible in every fissure. Eternity is not smooth—it is ruptured, interrupted, like faith in the night. And so, the cracks do not diminish the sacred—they deepen it.

Clay and the Breath of the Divine

Aleijadinho began with clay before stone. There is something intimate in that origin—the softness, the malleability, the immediacy of touch. Clay responds to warmth, to moisture, to breath.

In his work, we sense this intimacy preserved. Even the harder stone retains the softness of the original form. The divine here is not distant—it is formed with the palm of the hand, close to the ribs, like the shaping of Adam in the dust.

Sacred Asymmetry and Holy Imperfection

His sculptures are not perfect—and that is their genius. One shoulder higher, one eye deeper, one cheek more pronounced. These are not flaws; they are truths. Life is not symmetrical, nor is grace.

The asymmetry makes the figures human—and thus, reachable. Holiness, in Aleijadinho’s work, is not distant radiance but wounded proximity. Imperfection becomes the mark of the sacred.

The Earth as Witness and Material

The stones he sculpted came from the same earth where blood, sweat, and gold mingled. Minas Gerais was not just a place—it was a crucible. The red soil, the veined hills, the slave-built churches—all echo in the material itself.

His sculptures carry the memory of this land, shaped by both beauty and brutality. They are not just objects—they are witnesses. Testimonies carved from the very landscape of faith and pain.

Sculpting in Prayer, Living in Suffering

Aleijadinho’s workshop was not a studio—it was a chapel of anguish. Surrounded by assistants, half-crippled, he worked in silence, in devotion. Every figure carved was also a prayer offered.

Suffering shaped not just his body, but his vision. He saw the sacred not as triumph, but as endurance. His sculptures became stations of his own cross—each one a breath taken through pain.

Light, Shadow, and the Drama of Belief

In the sharp tropical light of Ouro Preto, his figures transform across the day. Light clings to the curves of garments, shadows deepen the crevices of brows. The drama of baroque becomes kinetic, alive in the motion of sun and moon.

Belief is theatrical in his work. Not for show—but because the divine always demands light and darkness. Revelation needs chiaroscuro. His figures do not glow—they burn quietly.

Expression Beyond Flesh

Though often restricted by the material and his condition, Aleijadinho found expression beyond realism. A tilt of the neck, a tension in the hand, a fold in the robe—these speak more than a thousand muscles.

Emotion is embedded not in facial mimicry, but in posture, in stillness, in gesture. A figure turned slightly away evokes abandonment. A hand half-lifted suggests doubt. The body becomes a scripture.

A Face Made of Dust and Fire

The faces of his prophets are carved not in ideal beauty, but in contradiction. Wrinkled yet ageless. Calm yet haunted. Their beards are windswept like Old Testament storms. Their eyes burn like candles forgotten on an altar.

These are not passive mouths—they bite prophecy. They howl divine fury. They whisper exile. They are not portraits—they are psalms in stone.

The Cross that Leans but Does Not Break

His crucifixes often depict a Christ whose body slumps, twisted, heavy. And yet—there is no collapse. The suffering bends the form, but grace keeps it from falling.

This tension defines Aleijadinho’s theology: salvation not as escape, but as endurance. Redemption is carved in the lean, in the tremor, in the almost—but never—the fall.

Emotional Chisel, Spiritual Hammer

Tools shaped matter, but emotion shaped meaning. Each gouge, each smoothing, each hollow was led by an inner necessity. The tools obeyed something deeper than design—they obeyed vision.

He did not sculpt merely with instruments, but with ache, with silence, with fire. His chisel struck not only stone—but the viewer’s soul. His hammer rang in the heart.

The Human as Altar

Aleijadinho turned the human form into the holiest altar. The back of a saint becomes a column. The robe folds become chapels. The open palm becomes a place to leave sorrows.

In this reversal, architecture kneels before anatomy. The body is no longer housed in churches—it houses the sacred. The human becomes the sanctuary.

When Form Kneels

Many of his figures kneel—not in submission, but in conversation. Their knees touch earth as if listening to it. They bow as trees do to storm—not to surrender, but to remain rooted.

This kneeling is not theatrical—it is intimate. A gesture of reverence, yes, but also of closeness. The divine is not above—it is beside.

Texture as Testimony

The texture of his stone is uneven, often coarse. It resists polish. It invites the fingers. These are not sculptures to be admired from a distance—they demand nearness, touch, connection.

The roughness tells stories. Of time. Of weather. Of belief. It refuses to be ideal. It prefers to be real. Texture, here, is not surface—it is narrative.

Architecture of Faith in a Body

In Congonhas, the prophets stand before a sanctuary—but they are sanctuaries themselves. They form a colonnade of conviction, a procession of carved psalms.

Each one is a cathedral of expression. Together, they are a choir of stone. The architecture extends not just through walls, but through ribs and mouths and robes that flutter like banners of faith.

Sculpted Testaments in Ouro Preto

Ouro Preto holds his legacy not in museums, but in streets, in stones, in stairways. His sculptures bleed into the city’s breath. They are not isolated—they are part of the liturgy of daily life.

Children pass them without fear. Elders weep before them. Tourists pause. The saints remain. They witness. They wait. They are testaments not only of art—but of a people’s enduring flame.

The Voice of the Baroque Echoes Still

Though centuries old, Aleijadinho’s voice still echoes—in wood, in dust, in the memory of sculpted devotion. His baroque is not gone—it has simply moved inward, into how we see, how we feel, how we seek the sacred in the scarred.

He teaches us that brokenness can be holy. That suffering can shape beauty. That a body in pain can still raise forms toward heaven. From clay to being—he sculpted us all.

FAQ – Understanding Aleijadinho and His Art

Who was Aleijadinho?

Antônio Francisco Lisboa (1738–1814), known as Aleijadinho (“the little cripple”), was a Brazilian sculptor and architect, considered one of the greatest artists of colonial Brazil.

Why is he called “Aleijadinho”?

He suffered from a debilitating disease (likely leprosy or a form of autoimmune condition) that disfigured his hands and feet. Despite this, he continued to sculpt with tools strapped to his limbs.

What materials did he use?

He primarily worked in soapstone and wood, materials readily available in Minas Gerais. His textures and finishes were deeply expressive.

Where can we see his work?

His most famous works are in Congonhas (the Twelve Prophets) and Ouro Preto, including churches and public sculptures.

What style did he work in?

Baroque and Rococo, but deeply personalized. His baroque was emotional, mystical, and uniquely Brazilian in tone and context.

What themes are central to his art?

Suffering, devotion, spiritual drama, and the human condition. He often sculpted religious figures with intense emotional and symbolic resonance.

Final Reflections – When Stone Becomes Prayer

Aleijadinho did not sculpt statues. He sculpted prayers made of dust. He carved voices into silence. He shaped the invisible ache of centuries into robes and brows and weary hands.

His work reminds us that beauty does not need perfection. That holiness can inhabit fracture. That even broken hands can hold heaven.

In every fissure, there is flame. In every weight, a whisper. From clay to being, he did not just sculpt forms—he sculpted the soul of a nation.