Frida Kahlo and the Thorns that Bloom from Pain

Contemplative Opening

Pain does not simply pierce. Sometimes, it blossoms. In the universe of Frida Kahlo, suffering is neither silent nor defeated—it is fertile. From every wound, a petal grows; from every scar, a root coils around the soul. She does not hide the hurt. She crowns herself with it, lets it climb her spine, allows it to blossom on her chest like a garden that never sleeps.

In The Thorns that Bloom from Pain, Frida does not offer a cry but a gaze—steadfast, unwavering, layered with thorns and hummingbirds, blood and stillness. She does not turn away from agony. Instead, she poses with it. She makes of it a canvas, a crown, a necklace. Pain becomes symbol, and in becoming symbol, it becomes eternal.

Table of Contents

- The Garden Beneath the Wound

- The Silent Crown of Spines

- Blood as Ornament, Not Warning

- The Hummingbird Between the Breasts

- Stillness Charged with Screams

- Frida’s Eyes as Mirrors of Defiance

- Botanical Martyrdom

- The Neck as Altar

- The Thorns That Replace Language

- Shadows Behind the Foliage

- Earth Colored Palette of the Body

- Self Portrait as Sacred Testimony

- A Feminine Via Crucis

- Emotional Textures and Symbolic Threads

- Pain That Blossoms in Stillness

- Frida’s Skin: Canvas and Confession

- The Weight of the Background

- Animal Witnesses of the Inner Storm

- The Intimacy of Decay

- Beauty Rooted in Suffering

The Garden Beneath the Wound

Frida’s body is not merely flesh—it is terrain. In her self-portraits, pain grows like a vine, winding around her neck, chest, and shoulders. The wound is not hidden but displayed, cultivated. It feeds a garden not of peace, but of resistance. In this particular image, we do not see a woman defeated, but one transformed into fertile soil.

The Silent Crown of Spines

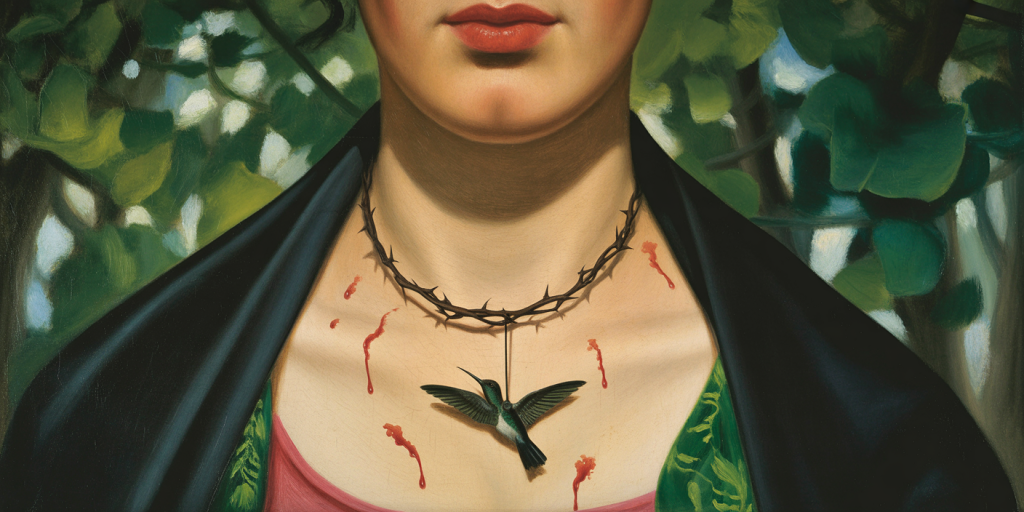

A necklace of thorns encircles her throat, not unlike Christ’s crown. But Frida does not kneel or bow. Her back is straight, her face lifted. The thorns pierce, yes, but they also frame. They highlight her stillness, her dignity. Pain becomes her halo. She is saint and soil, bleeding but blooming.

Blood as Ornament, Not Warning

The blood in Frida’s portrait is not a call for help—it is a brushstroke. It glistens along the neck, the skin, tracing the path of each thorn. There is no scream in it, only presence. Blood is the ink with which her suffering is written. In transforming injury into decoration, Frida claims ownership of the pain.

The Hummingbird Between the Breasts

Hanging from the thorn necklace is a black hummingbird—a symbol of hope, luck, love in Mexican folklore. But here, it is lifeless. It dangles, inert, like a relic drained of flight. It rests between her breasts, once symbols of life and nurturing, now a stage for silence. The bird becomes a contradiction: vitality suspended.

Stillness Charged with Screams

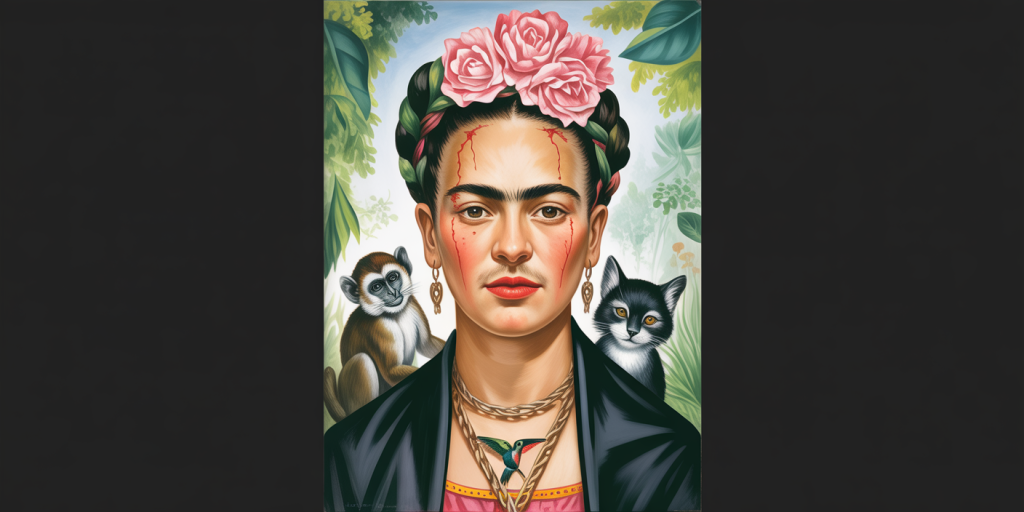

Frida’s face remains impassive, but everything around her vibrates. The monkeys, the cat, the foliage, the thorns—all seem caught in breathless tension. Her calmness is not emptiness but pressure contained. Behind the serenity, a scream is folded like a fan, ready to open but never released. Stillness becomes an emotional crescendo.

Frida’s Eyes as Mirrors of Defiance

The eyes never lie in a Frida Kahlo painting. Here, they meet the viewer directly. They do not plead, they do not flinch. They demand recognition. Her stare is a mirror: it reflects the discomfort of the beholder. It is the gaze of someone who has survived and will not be turned away.

Botanical Martyrdom

The flora behind Frida is not a garden of Eden but a jungle of survival. Leaves frame her like wings or blades. Nature here is not peaceful but complicit in her suffering. Even beauty becomes dense, suffocating. This martyrdom is not sacred; it is botanical, raw, rooted.

The Neck as Altar

The neck, so often a symbol of vulnerability, becomes a shrine. The thorns, the hummingbird, the blood—all converge there. It is a place of sacrifice, but also of ritual. The neck holds the head and the heart in tension. In Frida’s painting, it is where the invisible becomes seen.

The Thorns That Replace Language

Frida does not use speech to convey pain. She uses thorns. Each one is a word, each puncture a syllable. Her language is tactile, not verbal. The viewer reads her pain through skin, not through narrative. It is an alphabet of anguish, arranged in petals and points.

Shadows Behind the Foliage

Behind the greenery lies darkness. The background, though lush, is not welcoming. It suggests hidden eyes, unseen dangers. Monkeys peer from the leaves. A black cat looms like an omen. Nature is not separate from Frida—it watches her, and perhaps judges. The wildness behind her echoes the wildness within.

Earth-Colored Palette of the Body

The tones of Frida’s skin and surroundings are drawn from soil and stone. Ochres, greens, dark browns. These are not cosmetic choices but symbolic ones. Her body belongs to the earth. She paints herself not as porcelain but as mud—living, cracked, regenerative. Her palette is elemental.

Self-Portrait as Sacred Testimony

Frida’s self-portraits are never simply about resemblance. They are records. Testimonies. Each brushstroke says: I was here. I bled. I endured. In this portrait, she places herself not in myth or fantasy but in a moment of raw truth. Her face is altar, painting, and scripture.

A Feminine Via Crucis

Like a visual Stations of the Cross, Frida’s portrait walks the viewer through suffering. But this is a woman’s crucifixion—internal, private, bodily. She does not carry a wooden cross, but the weight of expectation, infertility, infidelity, immobility. Her pain is not theatrical; it is sacred.

Emotional Textures and Symbolic Threads

The textures in the painting—the roughness of leaves, the softness of skin, the sharpness of thorns—speak in silence. Every texture is emotional. Every edge cuts, every softness soothes. The threads that bind the thorns are not just physical but symbolic: ties of trauma, knots of memory.

Pain That Blossoms in Stillness

Frida does not thrash in agony. She sits. She holds the pain. This stillness is more powerful than motion. It is endurance without spectacle. Pain blooms in the unmoving body. She becomes a living altar where suffering flowers.

Frida’s Skin: Canvas and Confession

Frida’s skin is not painted to conceal, but to reveal. It is a confession. The smoothness is deceptive—beneath it lie surgeries, fractures, betrayals. She paints it with the reverence of someone documenting a sacred text. The body, wounded and whole, becomes an artifact.

The Weight of the Background

The foliage is not decorative—it is heavy. It presses in. It reminds us that even beauty has weight. Behind Frida, the world does not recede into distance; it leans forward, insistent. The painting closes in, making the viewer feel the intimacy, the inescapability, of pain.

Animal Witnesses of the Inner Storm

The monkeys, the cat, even the hummingbird—they are not mere companions. They are witnesses. Silent, symbolic, they reflect different aspects of Frida’s psyche. The cat, with its dark stare, suggests danger or sensuality. The monkey, playful or menacing. They surround her like emotions without names.

The Intimacy of Decay

There is beauty in this image, but also rot. Not visible, but sensed. The blood, the lifeless bird, the tightness of the thorns—all hint at slow decay. Yet Frida embraces this. She does not reject death or pain. She invites them to speak through her image.

Beauty Rooted in Suffering

Frida’s beauty is not conventional. It is carved from resilience. Her unibrow, her mustache, her steady gaze—all defy prettiness. But there is immense beauty here, one rooted in truth, in survival. Her pain does not diminish her image—it nourishes it. She blooms not despite suffering, but because of it.

FAQ

Who was Frida Kahlo?

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) was a Mexican painter known for her deeply personal and symbolic self-portraits. Her work explores themes of pain, identity, and femininity.

What is the significance of the thorn necklace?

The thorn necklace symbolizes suffering, sacrifice, and endurance. It recalls religious imagery while grounding it in Frida’s own physical and emotional pain.

Why is a hummingbird included in the painting?

In Mexican folklore, hummingbirds represent love and vitality. In this portrait, the dead hummingbird suggests lost love or vitality suspended in suffering.

What style did Frida paint in?

Her work blends elements of surrealism, symbolism, and Mexican folk art. Though often associated with surrealism, Frida insisted she painted her reality.

Why are animals included in her self-portraits?

Animals in Frida’s portraits serve as symbols and emotional extensions of herself. They embody aspects of her inner world, acting as protectors, omens, or silent witnesses.

Final Reflections – When Thorns Become Petals

Frida Kahlo did not paint pain to evoke pity. She painted it to transform it. In her hands, suffering became image, ritual, presence. Her thorns are not weapons—they are veins. They carry not blood, but memory. And in every puncture, a bloom unfolds.

In The Thorns that Bloom from Pain, we do not merely see anguish—we see its flowering. Beauty, here, is not smooth or easy. It is jagged, sacred, defiant. Frida does not whisper her sorrow; she frames it in vines, adorns it with eyes, anchors it in silence. Her portrait does not fade with time. It stares back, unblinking—a garden that bleeds and blossoms, endlessly.