Caravaggio and the Moment Apollo Trembled Before Love

There are silences that split the heavens. In one of Caravaggio’s imagined moments, the god of the sun, Apollo, bearer of golden light and immortal poise, does not conquer, does not sing. He trembles. Not from battle nor fear, but from that first piercing recognition of love—love uninvited, love inevitable. In Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro cosmos, even gods are flung into the mortal pangs of desire.

This is not a depiction of mythology but of intimacy caught in mythic flesh. The body of Apollo is still divine, but the eyes are suddenly human. Muscles glisten not with victory, but with vulnerability. A sliver of shadow cuts across his chest like hesitation. This is the tremor before surrender, painted in candlelight.

Table of Contents

- A God Before the Flame

- Flesh Gilded in Hesitation

- The Bow Forgotten in the Hand

- Caravaggio’s Palette of Revelation

- Light That Pauses on the Lip

- The Youth in the Gaze

- Composition as Temptation

- Myth Melted into Skin

- Drapery That Breathes Doubt

- The Architecture of Vulnerability

- Gold Against the Darkness

- When Hands Do Not Touch

- Eyes Lit by Longing

- The Silence Between Notes

- Divine and Desirous

- Eros in Baroque Flesh

- The Body as Question

- Carnal Shadows, Sacred Skin

- The Mirror Beneath the God

- When Desire Holds the Brush

A God Before the Flame

In this scene, Apollo is not surrounded by the sun—he is illuminated by a smaller flame. A candle, perhaps, or the sudden surge of Eros. Caravaggio renders the god not with distance but with proximity. The divine is close, almost tangible, almost trembling.

Flesh Gilded in Hesitation

Caravaggio’s brush dwells on the skin, letting light wrap around Apollo’s clavicle and shoulder. There is no rush. Every inch glows with the slowness of realization. The divine flesh is not armoured—it is exposed. And in that exposure, hesitation lives.

The Bow Forgotten in the Hand

One hand holds a bow, but loosely. It is not drawn. It is not aimed. Love, after all, has struck first. The god known for piercing hearts now knows what it is to be pierced. The weapon, like identity, slips.

Caravaggio’s Palette of Revelation

Rich ochres, deep crimsons, shadowed indigos—the palette is not about glory but about inner unfolding. The divine is not radiant in gold, but in the blush of knowing. The colors throb rather than shine. They speak in slow, warm pulses.

Light That Pauses on the Lip

Caravaggio’s light does not flood. It stops. It teases. It rests upon Apollo’s lip as if uncertain whether to kiss or retreat. The upper lip, slightly parted, catches just enough glow to seem mid-confession. This is not illumination—it is seduction.

The Youth in the Gaze

Apollo here is youthful, but not naïve. His eyes do not widen—they deepen. There is knowledge, and also the ache of being known. Caravaggio paints a gaze that is both invitation and caution, a gaze that remembers eternity but forgets immunity.

Composition as Temptation

The scene is arranged not in balance but in pull. The viewer is drawn toward a space just outside the canvas, just beyond Apollo’s shoulder—where the object of his trembling might be. The composition lures as the story does.

Myth Melted into Skin

Rather than costume the god, Caravaggio dissolves the myth into anatomy. The divine becomes the curve of a back, the tilt of a neck. Symbols are abandoned. What remains is pulse, heat, breath. The myth is no longer told. It is felt.

Drapery That Breathes Doubt

The fabric that clings to Apollo’s waist is not decorative. It clings like reluctance. Half-fallen, half-held, it reveals more than it conceals. The drapery becomes a metaphor: desire wrapped in hesitation.

The Architecture of Vulnerability

Apollo is built, yes—his torso a sculpture of light and muscle. But the structure leans, as if caught off guard. There is no heroism in his stance, only readiness to fall. Vulnerability becomes architectural. Caravaggio sculpts uncertainty.

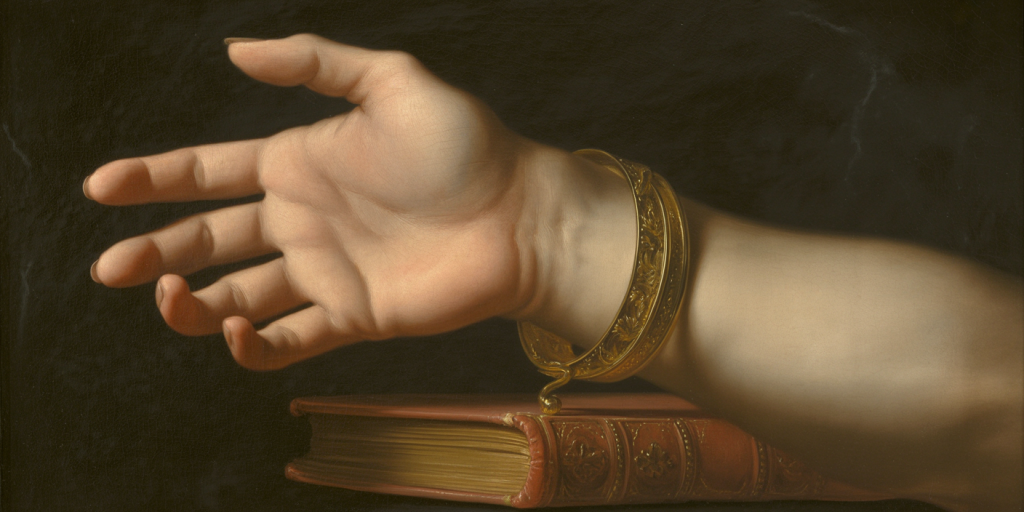

Gold Against the Darkness

What little adornment exists is gold—not as triumph, but as contrast. Against the cavernous dark, a glint of bracelet or hair. The effect is not majesty, but fragility. Gold becomes whisper, not proclamation.

When Hands Do Not Touch

There is no embrace in this scene. But the absence of contact throbs louder than touch. Apollo’s fingers hover, gesture, yearn. The negative space between skin and skin becomes the very site of emotion. Love lives not in union, but in approach.

Eyes Lit by Longing

The eyes in Caravaggio never simply see. They radiate. Apollo’s eyes are not fixed on a subject but pulled by a force. The longing is not directed but diffused. It makes the whole face ache.

The Silence Between Notes

Caravaggio knew music, and here he paints its silence. Apollo’s lyre is absent, yet his pose hums with the music that does not play. This is the rest between notes, the pause that holds the breath of all melodies.

Divine and Desirous

To be godly and desirous is a paradox, but Caravaggio makes it flesh. Apollo is not diminished by want—he is completed. The desire does not reduce his divinity. It humanizes it. This is not about falling. It is about trembling while still standing.

Eros in Baroque Flesh

Eros is not depicted, but his arrow has landed. In the curves of Apollo’s limbs, in the flush of cheek, in the half-held breath—the god of love is present. Not seen, but written in flesh. The baroque becomes erotic without vulgarity.

The Body as Question

Apollo’s form does not answer. It asks. It leans toward something unseen, offers no certainty. The body becomes an inquiry into feeling: What is this that makes the god tremble? Caravaggio lets the question breathe.

Carnal Shadows, Sacred Skin

Shadow crawls over Apollo, not to obscure, but to sanctify. The darkness blesses his skin, makes the exposed flesh sacred. Carnality and sanctity are not opposites in Caravaggio’s theology—they are married.

The Mirror Beneath the God

Though unseen, one feels a mirror must be nearby. Apollo’s self-awareness is palpable. He is both object and observer. This is not narcissism but reflection. The trembling is doubled: felt in flesh, seen in soul.

When Desire Holds the Brush

Caravaggio does not paint with detachment. His brush is gripped by longing. Every stroke aches. Every contour pulses. The love that Apollo feels, the tremble that overtakes him—it passes through Caravaggio’s own hands. The artist is not outside the scene. He is inside the tremor.

FAQ

Did Caravaggio actually paint Apollo in this scene?

There is no known painting by Caravaggio specifically titled or documented as Apollo trembling before love. This is an imaginative reconfiguration of his aesthetic applied to a mythological moment he never directly depicted, but could have.

What defines Caravaggio’s style?

Chiaroscuro (dramatic contrast of light and dark), raw emotional realism, theatrical composition, and sacred themes rendered with human vulnerability.

Was Caravaggio known for painting mythological subjects?

Yes, though less frequently than religious ones. His few mythological works, such as “Bacchus” or “Cupid as Victor,” are marked by sensuality, intimacy, and subversion.

What is the significance of the light in his works?

Light in Caravaggio is never neutral. It is emotional, directional, revelatory. It does not simply illuminate forms but uncovers truths—often uncomfortable.

Why associate Apollo with trembling?

Apollo is often portrayed as a symbol of order, reason, and poise. Depicting him trembling before love subverts this and reveals the vulnerability even gods cannot escape.

Final Reflections – Where the God Trembles

In Caravaggio’s universe, even the gods bleed. Even Apollo trembles.

This imagined portrait is not blasphemy. It is reverence made intimate. Caravaggio does not strip divinity of its glory—he clothes it in humanity. And in doing so, he lets us see ourselves in Olympus.

Apollo, trembling before love, becomes every heart caught between pride and surrender, beauty and ache. And Caravaggio, with candle and brush, captures that breathless second before the fall—where shadow curves around light, and the god, for one moment, becomes entirely, radiantly human.