The Body Melts into Space: Dalí and Bronze in Suspension

There are moments when time loses its footing, and flesh forgets its form. In the hands of Salvador Dalí, bronze—so often bound to the weight of permanence—surrenders to dreams. His sculptures do not stand still; they float, dissolve, evaporate. They are hallucinations cast into metal. They are thoughts that refused to remain invisible.

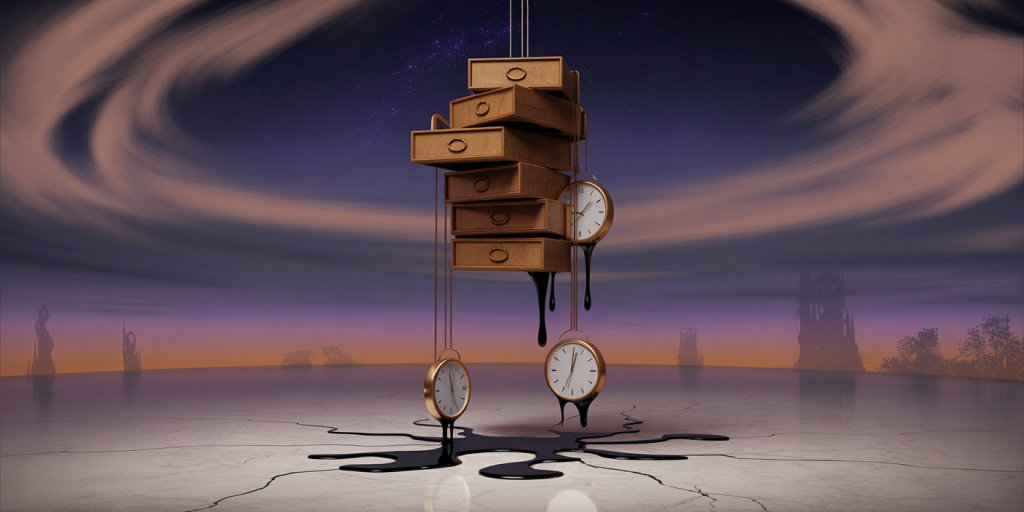

Dalí does not sculpt bodies. He sculpts the moment before they vanish. A melting clock, a figure pierced by drawers, a horse walking on crutches—these are not symbols to decode, but sensations to endure. They shimmer with delirium, stretch with desire, and collapse into the ether. In Dalí’s bronze, the body is no longer anatomy. It is memory, breath, absurdity—and faith.

Summary

- The Alchemy of Bronze Dreams

- Melting Flesh and Eternal Time

- When Gravity Becomes Thought

- Clocks That Bleed Through the Skin

- The Fluid Anatomy of Madness

- Crutches and the Architecture of Fragility

- Sacred Drawers in the Torso

- Angels Without Heaven

- Bronze That Yearns to Disappear

- The Eroticism of Distortion

- Reflections in a Dripping Mirror

- The Monument of Hallucination

- Light that Clings to the Absurd

- The Surreal Pulse of Stillness

- Bones That Remember Dreams

- Eyes Suspended Between Realms

- The Dali esque Shadow

- Sculpting the Immaterial

- Between Myth and Mutation

- When Metal Becomes Mirage

The Alchemy of Bronze Dreams

Dalí’s sculptures are not bronze as we know it—they are dreamstuff alloyed with subconscious heat. He transforms this ancient medium, traditionally reserved for permanence, into a carrier of impermanence. Each form is alchemical: the solid melted into motion, the eternal turned fragile.

Bronze, in Dalí’s hand, becomes fluid without losing weight. It floats, even as it casts shadow. It pulses, even as it stands still. It is no longer a substance—it is a symptom.

Melting Flesh and Eternal Time

In his iconic Dance of Time series, Dalí gives form to the hour as if it were made of skin. The clocks do not tick—they weep. They hang limply, folding into themselves, like exhausted hearts too long aware of mortality.

Time, here, is not measured—it is mourned. The flesh that melts with it becomes a companion, an extension of that temporal disintegration. What we see is not a watch, but a wound.

When Gravity Becomes Thought

Dalí’s figures defy logic. Some stand impossibly tall, supported by crutches that pierce their limbs. Others float in poses never meant for earthly stability. The laws of physics become whispers—guidelines rather than rules.

In this world, gravity is not a force, but a thought. The body follows not anatomy, but emotion. It slumps under symbolic weight. It arches in metaphysical resistance. The sculpture does not rest on the plinth—it hovers above our understanding.

Clocks That Bleed Through the Skin

The melting clocks appear again and again—not just over branches, but over bodies. They drip from shoulders, cover faces, wrap torsos. They suggest not only the passage of time, but its infiltration into the flesh.

These clocks are not timepieces—they are time itself. And time, in Dalí’s vision, is neither linear nor logical. It melts because memory melts. It folds because desire folds. It sinks because the soul is heavy.

The Fluid Anatomy of Madness

Dalí distorts anatomy not to destroy it, but to reveal its deeper nature. The human body in his sculptures stretches, twists, vanishes into itself. Knees bend where no joints exist. Arms emerge from folds of time.

This is not madness—it is clarity. Dalí shows us what the body feels, not what it looks like. In distortion, we find a new truth. The soul is not symmetrical. The mind is not a mirror. They are waves, echoes, screams made elegant.

Crutches and the Architecture of Fragility

The crutch is Dalí’s most poignant sculptural motif. It props up lips, torsos, angels. It appears where the form fails, where the spirit sags. It is both support and betrayal.

These crutches are not signs of weakness. They are maps of vulnerability. They mark the points where desire is too heavy, where ecstasy overwhelms. They are the scaffolding of surrealism—the structure behind collapse.

Sacred Drawers in the Torso

One of Dalí’s most evocative choices was to embed drawers into the human form. A chest opened in the belly. A small handle in the thigh. These drawers suggest the body as archive, as sacred cabinet.

What lies inside is not flesh—but memory. Desire. Secrets. The drawers are not to be opened—they are to be imagined. They invite speculation, not revelation. We are not meant to know everything. Only to feel the key turning in our soul.

Angels Without Heaven

Dalí’s winged figures rarely ascend. Their wings are heavy, symbolic, often drooping. They are angels burdened by thought, not lifted by faith.

These beings do not fly—they float. They remind us that belief is not always uplifting. That divinity can be exhausted. That in surrealism, even heaven is a question.

Bronze That Yearns to Disappear

Despite its mass, Dalí’s bronze feels on the verge of vanishing. The edges blur. The forms drip. The shadows stretch too far.

His sculptures inhabit the liminal state between being and unbeing. They are apparitions with weight. They are hallucinations held still. They want to disappear—but stay, just long enough for us to forget what permanence means.

The Eroticism of Distortion

Desire in Dalí’s bronze is never direct. It slithers. It softens. It exposes and conceals. Breasts turn into landscapes. Hips become horizons. The erotic is not in the detail, but in the gesture.

This is not sensuality—it is surreal seduction. The kind that happens in dreams, where nothing touches, but everything burns.

Reflections in a Dripping Mirror

Many of Dalí’s sculptural surfaces are polished to a high sheen. They reflect. But the reflection is never clear—it bends over curves, distorts in folds.

Looking into these bronzes is like looking into a mirror made of thought. You see not yourself, but the version your subconscious hides. You see what time has done to your silhouette.

The Monument of Hallucination

Dalí’s works are not small gestures. They are monuments—sometimes towering, always demanding. They celebrate the hallucination, give scale to the dream.

He dares to make madness monumental. Not to mock it, but to honor it. His sculptures do not fit in vitrines. They demand space. They demand sky.

Light that Clings to the Absurd

Dalí understood light. He knew how it would slip across bronze, how it would deepen shadows within drawers, how it would make the melting form shimmer.

Light in his work does not illuminate—it clings. It caresses absurdity with reverence. It makes hallucination feel real.

The Surreal Pulse of Stillness

Though still, Dalí’s bronzes pulse with possibility. They seem to be mid-motion—even mid-dissolution. One feels they could melt further, if not for our gaze.

This is the tension that defines his sculpture: the stillness that threatens to become something else. Something unnameable. Something divine.

Bones That Remember Dreams

The skeleton in Dalí is always half-visible. A rib pokes through. A leg curves like bone, not muscle. He reminds us that even dreams have a structure.

His bones are not morbid. They are foundations. They hold up the dream. They are what remains when fantasy has faded.

Eyes Suspended Between Realms

When Dalí’s figures have eyes, they are either wide with revelation or sealed in knowing. These are not the eyes of real beings—they are thresholds.

Looking into them is not to find truth, but to cross into something else. Something that floats, melts, unravels you.

The Dali-esque Shadow

Dalí’s bronze casts shadows that are as surreal as the forms. The elongation, the blurring, the angles—everything conspires to make the shadow a new sculpture.

The shadow is not secondary. It is an extension of thought. It completes the bronze in absence.

Sculpting the Immaterial

What Dalí achieves most remarkably is the impossible: he sculpts the immaterial. He gives bronze the quality of vapor. He carves not flesh, but feeling.

His sculptures are not about form. They are about the act of almost losing it. About the moment when the mind starts to reshape the body in its image.

Between Myth and Mutation

Many of his figures echo mythology—Venus, angels, elephants, dancers. But each is mutated, reimagined, reshaped.

They are not archetypes. They are transformations. Each myth melts into new meaning. Each symbol breathes with paradox.

When Metal Becomes Mirage

In Dalí’s hands, metal ceases to be metal. It becomes mirage—real but unreachable, fixed but ephemeral.

His bronzes teach us that art does not have to clarify. It can confuse, seduce, dissolve. It can melt, and still remain.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Salvador Dalí?

Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) was a Spanish surrealist artist known for his eccentric persona and groundbreaking works in painting, sculpture, and film. He remains one of the most iconic figures of 20th-century art.

Did Dalí create sculptures as well as paintings?

Yes. Dalí produced numerous bronze sculptures based on his surrealist themes, translating his melting forms, drawers, clocks, and figures into three-dimensional art.

What materials did he use?

Dalí worked extensively with bronze in sculpture, often combining it with gold leaf or polished patinas to accentuate surrealist qualities.

What are common symbols in his sculptures?

Melting clocks, crutches, drawers, angels, distorted human forms, elephants with long legs, and eggs—all part of his symbolic surrealist vocabulary.

What was the role of time in his art?

Time, for Dalí, was psychological and elastic. His melting clocks symbolize the unreliability and fluidity of time within dreams and human perception.

Final Reflections – The Bronze that Dreams

Salvador Dalí did not sculpt what was seen. He sculpted what was almost remembered, barely imagined, half-forgotten in the subconscious. His bronze is not cold—it sweats with fever. It dreams.

His forms do not seek stability. They melt. They float. They pierce. And in doing so, they reveal a truth beyond surface: that the body is not the end, but the beginning of imagination. That form is not fixed—but in flux. That in suspension, in distortion, in absurdity—art finds its truest shape.