The Skin of Narcissus Glows Under the Light of Salvador Dalí

Some reflections do not belong to water. They echo through the folds of the mind. In Salvador Dalí’s surreal cosmos, Narcissus is not merely gazing into a pool, but dissolving into it. The skin, luminous and aching, does not reflect—it melts. And in that melting, a new myth is reborn, shimmering with paradox and ambiguity.

In Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Dalí does not just paint a moment—he fractures it. Time collapses, forms echo themselves, and love becomes both blossom and bone. Narcissus is no longer a youth; he is an idea, an egg, a gesture fossilized and reborn. And his skin, glistening in Dalí’s unforgiving light, is both mirror and illusion.

Table of Contents

- Landscapes That Whisper of Obsession

- The Split of the Self

- Skin as Reflection and Relic

- The Gesture That Crystallizes Longing

- Dalí’s Palette of Psychological Fire

- When Shadows Drip Like Thought

- Hair That Crawls Like Memory

- The Narcissus Egg

- Surrealism as Emotional Dissection

- The Water That Remembers

- Bones Sprouting from Solitude

- A Body Carved by Light

- Texture of Hallucinated Desire

- The Double That Refuses Reunion

- Symbolism in the Dry Flower

- The Sky as a Theater of Silence

- Myth Through the Eye of Paranoia

- Flesh Turned to Stone, Emotion to Pattern

- Narcissus and the Eternal Gaze

- The Skin That Became an Idea

Landscapes That Whisper of Obsession

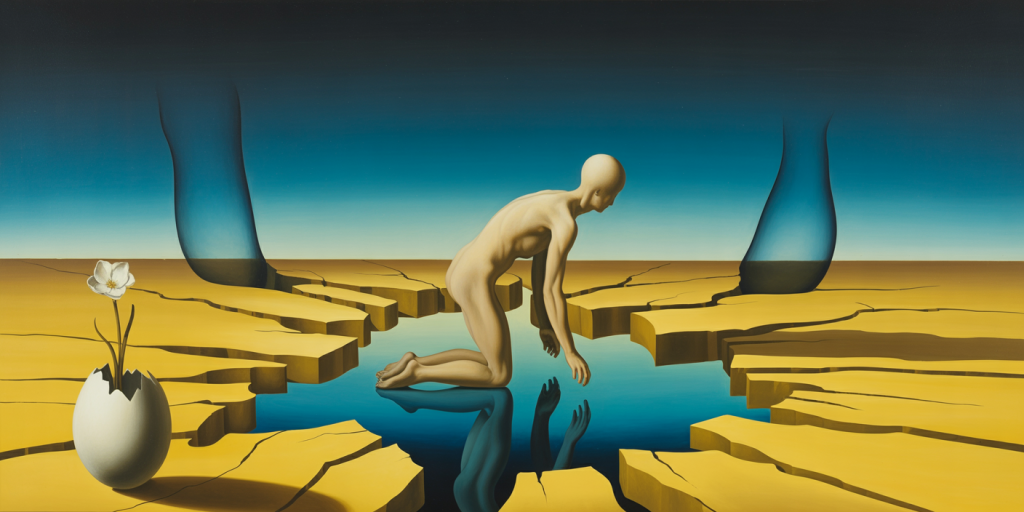

The painting opens with a terrain that is both exterior and interior. Cracked, golden soil stretches beneath a sky too still to be real. These are not landscapes of geography, but of psyche. Every hill is a thought, every crevice a buried desire. Dalí paints not a world, but an emotional topography.

The Split of the Self

To the left, Narcissus bends over the pool; to the right, a hand echoes his posture. But this is no mirror. It is a fracture. The self is not reflected—it is repeated, warped, estranged. Dalí refuses reunion. The split suggests the impossibility of self-love without transformation.

Skin as Reflection and Relic

Narcissus’ skin glows with a strange, internal luminosity. It is not the glow of youth, but of meaning placed upon flesh. It is both alive and fossilized. The contours shimmer with desire but remain immobile, like marble slowly remembering warmth.

The Gesture That Crystallizes Longing

The crouched posture is pure yearning. But Dalí traps it. The moment becomes eternal. Narcissus no longer moves—he loops. The body becomes a gesture in stone, the climax of desire never relieved. This is not romantic. It is obsessive.

Dalí’s Palette of Psychological Fire

The colors burn softly. Ochres and oranges dominate the earth, while shadows drip in deep blues and bruised browns. Flesh is lit not by sunlight, but by the temperature of hallucination. Every hue is the temperature of thought.

When Shadows Drip Like Thought

The shadows in the painting do not anchor. They melt. They stretch like time in a dream, dragging behind objects like echoes. They do not define space, they question it. In Dalí’s world, even darkness is distorted by desire.

Hair That Crawls Like Memory

The hair on Narcissus’ head seems almost to move. It clumps and curves in ways that feel alive. It does not frame the face—it invades it. Like memory, it is tangled, growing backward and downward. There is no innocence in this hair, only history.

The Narcissus Egg

In the mirrored hand-form rests an egg. From it, a flower grows. This is metamorphosis as metaphor: identity turned to potential, love turned to abstraction. The egg is the idea of Narcissus, unhatched and perpetual. The flower is the dream he will never live.

Surrealism as Emotional Dissection

Dalí does not illustrate the myth. He vivisects it. The emotional undercurrents are laid bare: vanity, loneliness, longing, dissolution. Surrealism becomes scalpel. Narcissus is not a boy by the water. He is a wound opened by sight.

The Water That Remembers

The pool below Narcissus is less a mirror than a witness. It does not reflect—it absorbs. The water is memory made liquid. It holds not just the face, but the feeling. In Dalí’s hands, water becomes a mind in motion.

Bones Sprouting from Solitude

The right side of the canvas turns desire into monument. Bones emerge. The hand is not warm but calcified. Where Narcissus had blood, his reflection has ivory. This is the price of obsession: a self so contemplated, it dies and solidifies.

A Body Carved by Light

Dalí uses light not to illuminate, but to sculpt. The glow upon Narcissus’ back is chiseled, architectural. His body seems built by light. This is not softness—this is a carving. The glow outlines the threshold between yearning and identity.

Texture of Hallucinated Desire

The surface of the painting feels dry, like desert skin. Every texture is heightened, yet intangible. Dalí paints the sensation of hallucination—hyper-real, but emotionally unstable. Touch becomes both invitation and threat.

The Double That Refuses Reunion

Unlike traditional depictions of Narcissus, Dalí’s version avoids symmetry. The figure and the hand are echoes, not twins. Reunion is denied. The self, split, remains divided. Love of the self, here, leads to fragmentation, not completion.

Symbolism in the Dry Flower

The flower that emerges from the egg is dry, almost brittle. It is not blooming in joy, but preserved in loss. This is not rebirth. It is remembrance. Love becomes relic, not renewal. The flower is the last breath of a feeling embalmed.

The Sky as a Theater of Silence

Above the strange terrain floats a sky of deliberate stillness. There are no clouds, no movement. It hovers like a curtain pulled back. This is the theater of myth, and also of stasis. Dalí suggests that the drama is internal—the sky only watches.

Myth Through the Eye of Paranoia

Dalí once described his method as “paranoiac-critical.” Here, that paranoia manifests as duplicity, as forms repeated and estranged. The myth is no longer a tale—it is a symptom. Narcissus is no longer a figure. He is a diagnosis.

Flesh Turned to Stone, Emotion to Pattern

What was once body is now object. The hand is polished, dead. The transformation is not miraculous—it is surgical. Dalí turns emotion into pattern, passion into fossil. Love becomes a thing to be displayed.

Narcissus and the Eternal Gaze

Narcissus cannot look away. The gaze is a loop, infinite. Dalí paints the prison of fascination. Narcissus will never rise. He will only reflect. The light on his skin is not life, but spotlight. He is the actor and the statue.

The Skin That Became an Idea

In Dalí’s vision, skin is not only surface—it is symbol. It glows, but not with health. It glows with meaning. It is idea made flesh and then dissolved again. The skin of Narcissus is not touched. It is translated.

FAQ

Who was Salvador Dalí?

Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) was a Spanish surrealist artist known for his eccentric imagery, technical skill, and exploration of dream, identity, and subconscious themes. He was a central figure in the Surrealist movement.

What is “The Metamorphosis of Narcissus”?

It is a painting created in 1937 by Dalí, inspired by the Greek myth of Narcissus. The work shows a surreal reinterpretation of the myth, with symbolic and duplicated imagery exploring identity and self-obsession.

Why are there two figures in the painting?

One is Narcissus crouching by the pool; the other is a stone hand holding an egg with a flower. This represents the duality of self—the physical and the symbolic, the desire and the result of that desire.

What is the role of light in the painting?

Light in this work sculpts the form, emphasizes transformation, and creates surreal drama. It is both emotional and narrative, shaping the way we perceive flesh and reflection.

How does Dalí’s version differ from classical depictions of Narcissus?

Dalí avoids romanticism. Instead of illustrating the myth, he deconstructs it. He turns the emotional core of the story into a surreal and symbolic dissection of ego and longing.

Final Reflections – When Light Writes the Myth

Narcissus, under Dalí’s hand, becomes more than myth. He becomes metaphor.

His skin, glowing beneath impossible light, becomes the surface upon which identity is written and erased. Dalí does not let us pity him. He invites us to see ourselves—reflected, distorted, doubled.

In this metamorphosis, love turns inward and becomes fossil. The flower blooms not from joy, but from obsession. And in that glowing skin, in that stillness too vivid to live, we feel the warmth of a myth that has not died, but molted into meaning.

Narcissus never drowns. He dissolves. And in that dissolution, Dalí finds a mirror that stares back forever.